May 08, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: Popular and Hot

An excerpt from an essay I recently read:

Sure, I know what the student was getting at, but as I read it, I couldn't help but imagine someone saying, "Man, get a load of the social programs on that Sweden! That's HOT!"

May 01, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: Second Best

A sign left over in our department's lounge from Graduate Student Appreciation Day a few weeks ago:

Enjoy your time on top, Poultry Science graduate students; we're gunning for you next year! Seriously, though, kudos to whomever added the "2nd" to the sign. I think it sums up the disillusionment of the average graduate student quite succinctly.

April 30, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: Reading Day

It's Reading Day today -- the day off between the end of classes and the beginning of final exams -- and about an hour ago, I passed a student (not my own) who was casually strolling across campus and smoking a blunt, the unmistakable scent of marijuana lingering behind him.

I can only assume that he had finished all his required readings.

April 29, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: The envelope, please

And the award for Worst Argument in Favor of Having an Exam Grade Changed in an Introductory Political Science Course goes to...

"I knew the right answer was A and I meant to circle it, but I accidentally circled D instead. Can I get credit for that?"

Let's have a big round of applause, ladies and gentlemen!

April 16, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: Academic Freedom

Students for Academic Freedom placed an advertisement in the campus newspaper yesterday that included the following text:

Yikes -- I hope an introductory American politics class falls under the classification of "some similar subject." After all, I had kinda planned to make mention of Iraq (and maybe even President Bush) at some point when we started our unit on foreign policy next week.

For extra added fun, check out Students for Academic Freedom's tips on how to research your professors' voter registration records and report them back to SAF.

April 01, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: The Fake Answers

Just in time for April Fools' Day!

Coming up with good multiple choice questions for an exam isn't that hard. The hard part is coming up with all the fake answers -- you know, the multiple choice options that aren't correct. On the one hand, you have to make sure that they're not too good; in other words, you don't want the fake answers to be close enough to correct that they confuse rather than test the students. On the other hand, they can't be too ridiculous either, or the students will see straight through them to identify the correct answer whether they've studied or not.

There's something to be said, however, for having a bit of fun with the fake answers. For instance, I had a history professor as an undergraduate that would often include a Frenchman by the name of Marquis de Loofru in the multiple choice answers on his exams. Marquis de Loofru..."de loofru"..."u r fooled." Get it? I always got the impression that the professor derived a great deal of joy from the instances when students actually chose the Marquis as the correct answer on his exams. Then again, he also took great pleasure in doing his best HL Mencken impression when students said something less-than-correct in class, calling them "boobs" and "nincompoops" while grinning like a jackanapes. But, I digress.

Taking a cue from that professor, I realized early on that I needed a good running fake-answer gag when I began teaching -- to entertain myself while writing and grading exams if nothing else. Eventually, I decided that my go-to fake answer was going to be...the Cone of Tragedy! I actually lifted the name from a broken-down carnival ride featured in an old computer game, figuring that it should be good for a few laughs. Before long, it was showing up as a potential answer in questions like this:

- Occam's Razor

- The Allegory of the Cave

- The Prisoners' Dilemma

- The Cone of Tragedy

- The Faustian Bargain

Eventually, the professor I worked with noticed that the Cone of Tragedy kept make repeat appearances on the exams. He asked about it, and I reluctantly explained the joke. Much to his credit and my surprise, he loved it and told me to keep using it. Before long, it became a competition between the two of us -- who could come up with the most ludicrous way to work the Cone of Tragedy into our exams. Five years later, we both continue to mention the Cone whenever the opportunity presents itself. For instance, just last week, I asked my students on an exam to identify the mutually supportive networks that arise in U.S. government between bureaucratic agencies, interest groups, and legislative committees with jurisdiction over a particular issue or policy area. Most of them correctly chose "iron triangles" as the answer, but one student decided to go with "cones of tragedy" instead.

The story doesn't end there, however. In recent months, I've spent quite a bit of time researching decision-making heuristics in international relations. In particular, I've been trying to determine why leaders insist on pursuing courses of action that they know are risky and unlikely to succeed when a rational individual would clearly do otherwise. It seems that in many cases, what happens is that the decision-maker starts out by making a bad decision and then continues to follow up that initial mistake with a series of further miscues in an attempt to "make things right," ultimately sending things spiraling out of control. I'm at the point now in my research where I need a catchy name to describe this decision-making fallacy, and only one springs immediately to mind: the Cone of Tragedy.

I think it's safe to say that I'll win the competition with my mentor if I can successfully incorporate the Cone into a peer-reviewed journal article. Heck, if I keep it up maybe the Cone of Tragedy could even make the transition from fake answer to real answer one of these days.

March 31, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: Pop Quiz

I asked my students to identify at least one interest group on an unannounced quiz earlier today. A small minority -- albeit large enough to register as somewhat disturbing -- listed NAMBLA. I guess I can always hope that they were referring to the National Association of Marlon Brando Look Alikes.

Thanks for doing your part to raise social awareness, South Park.

March 19, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: Note to Self

Dear Jess,

You are well aware of the fact that you can't leave the classroom while giving an exam for fear that the students might cheat in your absence. Therefore, in the future, I would counsel against drinking an entire 20-ounce bottle of Diet Coke during the first five minutes of the exam, knowing that you're not in a position to excuse yourself to go to the restroom for at least another 45 minutes.

In closing, any permanent damage suffered by your bladder this morning was your own damn fault.

Sincerely,

Jess

March 15, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: The Shoe's on the Other Foot

I experienced one of my first (of what is sure to be many) absent-minded professor moments earlier today. As I was walking across campus this morning, on my way to teach my class, I noticed that one of my shoes felt a little looser than the other. I looked down, only to discover that I had managed to leave the house wearing mismatched shoes. No, not socks. Shoes. I was wearing a clog on my left foot and a fake Birkenstock (Fakin'-stock) on the right.

Obviously, I couldn't go in front of my class with mismatched shoes; I'd never reestablish any sense of authority after that faux pas. I briefly considered teaching in my socks, but eventually decided that I might have just enough time to zip back home, change shoes, and get back to campus before my class started. I made it with about two minutes to spare.

If nothing else, this incident only serves to reinforce the fact that I definitely chose the right profession.

March 05, 2004

Tales from the Classroom: Prospective Students

My department asked several graduate students, myself included, to meet this afternoon with a group of prospective students considering entering the MA and Ph.D. programs next semester. I've always thought that leaving prospective students alone with current students is a somewhat less than prudent strategy. After all, you're unlikely to find a more disgruntled group of people than a bunch of overworked and underpaid graduate students. We did our best to put a positive spin on the program, though.

When asked how much work the average class requires a week, we confessed that it's usually at least a book a week per class, but noted that you eventually pick up some handy speed-reading skills along the way. Plus, no matter how much work we're assigned, we were careful to point out that it's not nearly as bad as the average "real world" job. When asked if our assistantships paid enough to get by, we tried to stress the low cost of living in town. Plus, we aren't in graduate school because of the money we're making -- or the money we hope to make later if we land a job in academia. If we were interested in money, we would have gone to law school. We're in graduate school because we love the subject matter. As one of my colleagues pointed out, we'd probably all be sleeping on park benches somewhere if we weren't graduate students.

We did try to warn the prospective students that studying political science in this day and age isn't quite the same thing as simply studying politics. For instance, the former requires significantly more mathematical training than the latter.

Eventually, however, one one of the prospective students got around to asking the $64,000 question: "So, do you guys feel like you made the right choice coming here?" After spending the past hour doing our best to paint the department in a positive -- albeit honest -- light, none of us could produce an answer to this simple question. Instead, we just glanced around at one another uncomfortably for a few moments before someone finally began to discuss the fact that the university compares favorably to other similarly-ranked schools around the country. None of the current students, however, was willing to go on record categorically affirming that coming to the university to study was a good idea.

That's graduate students for you. I'm sure that you'd find the same thing at Harvard.

March 01, 2004

Tales from the Classroom XV: Knit Picking

I'm starting to think that my pop quizzes are too easy. Today, one of my students finished in about thirty seconds, reached into her bag, pulled out some needles and a ball of yarn, and proceeded to knit (on a scarf?) for the next three and a half minutes.

February 26, 2004

Tales from the Classroom XIV: The Secret to Good Teaching

After spending the past few years teaching college classes, I believe that I have finally arrived at the Secret to Good Teaching. As far as I can tell, good teaching consists of either:

- knowing a lot about the subject matter, or

- successfully creating the illusion that one knows a lot about the subject matter.

It turns out that the answer is really quite simple: anecdotes.

That's right -- the key to making students believe that you know what you're talking about (assuming you don't) is to pepper your lectures and discussions with anecdotes about the material and other witty asides. For instance, if you're teaching a chemistry course, the students will be wowed if you bring up the fact that Marie Curie eventually died of radiation poisoning. Or, if you're teaching a history course, you can bowl them over with the fact that Teddy Roosevelt once wrestled a grizzly bear in the White House Rose Garden for control of the Panama Canal. I think. The details aren't really that important.

What is important, however, is that the teacher exhibits that he or she can go beyond what's in the textbook, showing a fundamental familiarity and comfort with the material. Just think back on your own education. Aren't the teachers who knew all the interesting stories trivia the ones who you remember most fondly?

Of course, you're probably saying to yourself, "Doesn't the liberal use of anecdotes, by its very nature, require substantive knowledge of the material?"

That's certainly one approach, but I have discovered a second way, dear readers, and that is the true Secret to Good Teaching (when actual knowledge of the subject matter isn't an option, of course).

Most textbooks include their own anecdotes that are relevant to the subject matter (it seems that textbook authors have also stumbled onto the Secret of Good Textbook Writing). Unfortunately, the students -- in theory -- are also reading the textbook for any given course, so they will most likely be able to detect if their teacher is simply repeating the same trivia that was already presented in their weekly reading assignments.

Even if the students are reading their textbook, however, it's a virtual lock that they aren't reading multiple textbooks on the subject. And that, dear readers, is the Secret to Good Teaching: consulting multiple textbooks to aggregate a wide range of anecdotes in order to create the illusion that one knows a lot about the subject matter.

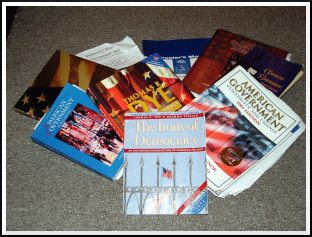

For instance, I consult no fewer than nine American politics texts in preparation for each of my lectures to gather every anecdote possible to supplement the "nuts and bolts" of the lecture itself. Don't believe me? Here's the full spread:

By the time I've read six or seven chapters on the topic of, say, interest groups, I'm armed with enough anecdotes to last me through a week of lecturing -- anecdotes that the students haven't already read in their own textbook. Sure, it's a time consuming process, but nobody ever said that teaching was easy. Best of all, every textbook that a teacher reads brings him or her closer to the ideal situation of actually knowing something of substance about the subject matter. It's a win-win situation!

So, now that you know the true Secret to Good Teaching -- using multiple textbooks to cull anecdotes and other trivia, thus creating the illusion of knowledge -- go forth and educate, dear readers!

February 20, 2004

Tales from the Classroom XIII: Just the facts, ma'am

You can learn a lot sometimes just by reading the work submitted by students. For instance, I've seen an entire essay exploring last year's controversy in Alabama over the "Ten Amendments," in which a student argued rather convincingly that the state judicial building should have the right to display the Bill of Rights since it is, after all, an important document in American history. I've also seen a student spend the better part of a five-page essay discussing the historic Al Smith presidency of the 1950s, examining how President Smith's disastrous policies ultimately resulted in the Great Depression. How, pray tell, does one grade that?

Ever wonder how the judicial process works in the Supreme Court? Rumor has it that the Justices preside as judges, the 535 members of the combined houses of Congress serve as the jury, and the President of the United States acts as the prosecutor. Oh, and I'm sure there are probably hobbits involved somehow, too.

Heck, I've seen an entire essay written about the origins of the Vitamin War. I assumed the student was talking about the unforgettable skirmish in which King Vitaman led his C battalion against the evil forces of Scurvy, but it turns out he was actually thinking of some obscure war that took place in Southeast Asia a few decades ago. I guess I'll just chalk that one up to a "Replace All" mistake while spellchecking in Microsoft Word.

I heard what remains my favorite "alternative history" back during my time as an undergraduate, though. It was during a modern European history class, and we were covering World War II. The professor had just finished reading an excerpt from Winston Churchill's famous "we shall never surrender" speech and concluded by posing the rhetorical question, "And did Great Britain surrender?"

Much to everyone's surprise, one of my classmates chimed in with the answer.

"Yes."

Now, I should note that this was an upper-level class consisting exclusively of history majors. The student in question, if I remember correctly, was a third-year history major at the time. That being said, the professor was justifiably taken aback by his response and decided to probe the matter a bit more deeply.

"So, after losing the Battle of Britain, England ended up surrendering to Nazi Germany?"

"Yes, sir."

"And Germany occupied Great Britain?"

"Yes, they did."

"And then went on the win the Second World War?"

"No, the United States eventually went over, liberated the British, and won the war."

Take that, Socratic method! In the student's defense, however, at least he got that part about the Nazis not winning World War II correct. For his part, the professor handled the increasingly ridiculous situation about as smoothly as possible, suggesting that the student had apparently misspoken and must have actually been thinking of France (which anyone who was in the classroom realized was quite obviously not the case).

It truly warms my heart to know that the student in question went on to earn the same degree that I did. Sigh...

February 11, 2004

Tales from the Classroom XII: Called Out

We discussed the establishment clause of the First Amendment today in class and ended up on the topic of the controversy over the phrase "under God" in the Pledge of Allegiance, and I couldn't help but think back to covering the same topic last semester. During that discussion, much like this morning, I brought up the fact that "under God" was not originally part of the pledge, but rather was added by Congress during the Eisenhower administration. As I said this, I noticed that one of my students made a snorting sound and rolled his eyes. Curious about his response, I asked him if he had a comment. It turns out that he did.

"That's not true. I'm pretty sure it was always in there," he said.

Honestly, I was more than a little taken aback. Had he just called BS on me in the middle of class? When teaching, I try to encourage critical thinking and I'm accustomed to having students question what's in their readings as well as the opinions expressed in class. I'm not, however, accustomed to having them challenge me on the facts -- especially when I had double-checked before class and knew that I was correct. Still, I was at a bit of a loss as to how I should respond to the student.

"Um, uh..." I stammered. "I'm relatively certain that the phrase was added during the Eisenhower administration."

"Whatever," he said, rolling his eyes again. "I don't think so."

Evidently, he wasn't buying it. To make matters worse, the rest of the class apparently wasn't familiar with this particular historical tidbit either and therefore couldn't offer any backup.

Ultimately, I settled for telling him he could look it up and confirm it if he wanted and decided to press ahead with the discussion. Still, the remainder of the discussion was colored by the fact he had introduced doubt among the class regarding a central point of the debate over original intent, essentially creating a scenario in which it was basically my word against his.

Looking back, I guess there wasn't really a better way to handle the situation. Of course, I could have just yelled "Wrong!" when he challenged me, à la John McLaughlin of The McLaughlin Group fame. Or, perhaps a simple, "You -- never talk again!" would have sufficed.

I never found out whether or not the student got around to checking the facts and came around to my point of view (if you can call a clear statement of fact a "point of view"). I have to admit, though, that I was definitely on the lookout for any rolling eyes when I repeated the fact in class today -- just in case.

February 04, 2004

Tales from the Classroom XI: German for "The Boot"

I made it through showing the 1981 German film Das Boot to a class yesterday afternoon without making a single joke about its fictional (?) X-rated counterpart, Das Booty. Maturity, thy name is Jess.

January 28, 2004

Tales from the Classroom X: Snow Day

As a result of Monday's unexpected ice storm, university officials ended up canceling classes for the day. Unfortunately, they waited until 8:30AM to make the decision -- after eight o'clock classes were well underway and several more students and university employees (myself included) were already traversing the icy roads to campus. That being said, the following letter to the editor showed up in the campus newspaper today:

All of these instances would be acceptable if it were not for the fact that I received very little sleep the night before due to my belief that school would be canceled.

It is time that the University realizes it must honor the precedents which it sets. Students should not, and hopefully will not, accept further discrepancies in school policy.

The consensus among my friends in the department is that the letter must be a joke -- due in large part to the laughable complaint about hands so cold that the student couldn't take notes (it was just barely below freezing) and the indignant admission that the student stayed up too late the night before under the assumption that class would be canceled. Whether intentional or not, though, it's still unquestionably chuckle-worthy.

Meanwhile, I can't help but recall a controversial school cancellation from my own time as an undergraduate.

I attended a small college as an undergraduate where well over 75 percent of the student body lived on campus. It was during my junior year, right around this time of year, that a huge snowstorm hit and dumped roughly three feet of snow on the area, knocking out electricity for the entire campus for a couple of days in the process. Needless to say, the school canceled classes as a result. After all, how could you hold classes when there's no electrical power on campus?

Well, it turns out that all it takes is a little determination and an up-to-date student directory.

I was taking a microeconomics course at the time, and we had a midterm exam scheduled for the morning after the big snow and resulting power outage hit. Naturally, when school officials canceled classes, the general assumption among my classmates and me was that the midterm would be postponed, as well. Not so.

I woke up around seven o'clock the following morning to the ringing of my phone. Picking it up, I was surprised to hear the voice of my microeconomics professor on the line. He said that he just wanted to call and remind me about our midterm at eight.

"Oh, Dr. So-and-So, you must not have heard. Classes are canceled. We don't have power on campus."

"I've heard. We're still having the exam. Everyone can walk to class; the snow's not that deep."

"Um...well, they announced that classes were canceled yesterday afternoon. If we even wanted to study after six o'clock in the evening, it would had to have been by candlelight. Plus, without power, there's the whole alarm clock issue --"

"We're having the midterm," he interrupted. "You've know about it for the past two weeks. Not having power last night is no excuse for not being prepared."

"But...um, classes are canceled, Dr. So-and-So. They announced it yesterday."

"I'll see you at eight."

Click.

Being the dedicated student that I was/am, I rolled out of bed, got dressed, and trudged through the snow to class (uphill, both ways). About half the class actually made it and, while we weren't particularly happy about it, we took the midterm. Meanwhile, the professor assigned zeros to the students who didn't show up. Naturally, when the school reopened a day or two later, the dean informed him that failing half the class wasn't going to fly and that he would need to offer a make-up exam to anyone who wanted it. The professor continued to resist the order until the dean made it clear that it wasn't exactly a matter open to debate, at which point the professor finally relented -- after explaining to the class that the dean had forced his hand and that he wasn't particularly happy about it. As a postscript, from what I understand, the professor's contract wasn't renewed the following year. I never found out if his infamous snow-day exam had anything to do with it, but sadly enough, it probably wasn't even in his top five or six offenses since he came to the school. Yeah, he was one of those professors.

Anyway, that's the story I told my students this morning when a few of them complained that they nearly broke their necks on the way to class on Monday morning before they found out that the university was closed. I think it made them feel a little better.

January 12, 2004

Tales from the Classroom IX: Going Blank

Typically, I lecture to my classes without the aid of prepared notes. Well, that's not entirely true. I usually take in a half-page outline so I'll be sure to hit certain key points, but otherwise, I find that I'm far more spontaneous--and in turn less boring--when I lecture extemporaneously. Of course, this without-a-net approach to teaching is not without its risks. For instance, while lecturing on the philosophical roots of American democracy this morning, the unthinkable happened.

I went blank.

We were discussing Thomas Hobbes' writings on human nature, and I decided to share with the class his famous description of life in the state of nature as "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." While I began the quote properly with the "solitary" and "poor" parts and knew it ended with "short," I completely blanked on the stuff in the middle. Now, that's not such a big deal in and of itself, but what was odd was the adjective that a little voice in the back of my head kept insisting I was leaving out: lemon-scented.

Yep, for some inexplicable reason, it was all I could do to keep from blurting out that Hobbes described the state of nature as "solitary, poor, lemon-scented, and short." So, while my students sat there, pens at the ready, I was having a Jan Brady-esque internal dialogue with myself that went something like this:

"Say lemon-scented! It's lemon-scented!"

"I'm pretty sure it's not lemon-scented."

"Yes, it is! It's always been lemon-scented! Say it! SAY IT!"

"Never!"

Eventually, I managed to right myself and get back on course by prompting the students to finish the quote along with me (heh heh). When it was all said and done, I'm relatively certain that they were none the wiser to my brief memory lapse. Nevertheless, I can't help but think how much more pleasant Hobbes' state of nature would have been with a bit of lemony freshness to get rid of the musty odors that accompany a good old-fashioned "warre of all against all."

December 16, 2003

Tales from the Classroom VIII: The End of the Semester

I'm staring down a stack of 110 essays, roughly four to five pages each, that need to be graded by Thursday morning. All the end-of-semester work seems worth it, though, when I receive emails like this one:

November 23, 2003

Tales from the Classroom VII: Teachers are People, Too

Much like my parents, I've spent my entire life showing up for everything--appointments, meetings, parties--ten minutes early, and my classes are no exception. Unfortunately, a person can only spend so long writing a lecture outline on the chalkboard and mindlessly shuffling through papers before class starts. Sooner or later, I have no choice but to engage my students in casual conversation while we're waiting for class to begin--that is, unless I just want to stand there behind the lectern and stare off into space vacantly (the merits of which are perhaps underrated).

As an instructor, however, striking up a conversation with the class isn't quite as easy as it sounds. After all, many of the students--especially the freshmen--haven't come to the realization yet that I'm a real, live human being with a wide range of interests and not just that guy who grades their exams and seems really interested in politics for some reason. That being said, I've tried chatting about current events with my students on occasion ("How about that kooky California recall, huh?"), but they tend to interpret such discussions as sly attempts on my part to sneak a few extra unwanted minutes of political science into their days and, in turn, don't appreciate it one bit.

On the other hand, idle chitchat doesn't seem to work all that well either. When I ask my students if they've seen Matrix Revolutions yet or if they're planning to go to the big game over the weekend, I can't help but feel that I'm coming off a bit like Dr. Evil in Austin Powers. "I'm with it. I'm hip." <insert creepy, robotic Macarena>

In a way, it's similar to when I bump into my students in public. When they see me outside of the classroom, their first reaction is usually surprise ("What are you doing at Old Navy?!?"), closely followed by fear, as if I've made a point to come to Chili's during their shift to talk to them about their performance on the most recent exam and not for the chicken soft tacos. Eventually, however, they settle on a sense of novelty as they begin to feel like they've not only unraveled a bit of the conundrum that is their Intro to American Politics instructor ("Aha...so he likes performance fleeces/chicken soft tacos."), but also discovered my deepest, darkest secret.

As it turns out, when I'm not teaching, I sometimes wear--brace yourselves--jeans and a t-shirt. Scandalous, I know.

November 15, 2003

Tales from the Classroom VI: Sonic Assault

As if yesterday's lesson plan alone wasn't enough to make teaching a challenge, about five minutes into my afternoon class someone from outside the building began blaring (on a car stereo?) Billy Joel's "Uptown Girl" so loudly that I actually had to speak up in order to be heard over it. Now, I should note that this wasn't just a few seconds of the song as a car drove past the building, but rather the entire three minutes and sixteen seconds--start to finish. Not surprisingly, we never covered that particular dilemma in any of my teaching seminars. Something tells me that Socrates himself couldn't lead a fruitful discussion under such torturous conditions.

Then, as if the scenario wasn't odd enough already, the sonic assault promptly ended when the song was over. It didn't fade out as a car drove into the distance, and no other song began playing when the track finished. It just ceased, as if the listener had gotten his or her "Uptown Girl" fix and was now sated and ready to carry on with the day. At the risk of sounding paranoid, if I didn't know better, I would think that someone was messing with me.

On a more positive note, at least it wasn't "Just the Way You Are."

November 14, 2003

Tales from the Classroom V: Jess' Political Grab Bag

Topics on the slate for today's 50-minute discussion:

- The impact of the economic upswing and war in Iraq on Democratic campaign strategy

- Howard Dean's decision to opt out of public funding

- Campaign finance and the influence of money in politics

- The roles of the media in American politics

- Debating the "liberal bias" in the media

- Bush v. Gore: evaluating the 2000 election and the function of the electoral college

October 17, 2003

Tales from the Classroom IV: Profanity

After one of my students employed a rather crude sexual euphemism during our discussion of presidential popularity earlier today (guess which president we were talking about!), it seems somewhat apropos to reflect on just how commonplace profanity has become in the classroom these days.

I should begin by saying that, unlike some professors, I never use profanity when I'm teaching. On the one hand, I think it sets the wrong tone for mature, scholarly discussion, and on the other, it's just not my style. Nevertheless, my students are oftentimes more than willing to pick up the slack. For instance, it's typical to hear students compare a political stance--say, opposition to keeping the phrase "under God" in the Pledge of Allegiance--to bovine (or, if they're feeling particularly bold, equine) excrement. I've even had a few students drop the dreaded f-bomb in the middle of a discussion--some by accident and others completely unapologetically. Sure, it's completely inappropriate for students to use profanity in the classroom, but I'm at least willing to give them the benefit of the doubt as long as they don't make a habit of it. After all, we frequently discuss controversial issues in class--abortion, First Amendment rights, affirmative action, and so forth--and tempers tend to run high about such topics, causing students to blurt out an opinion without quite thinking through what they're about to say prior to saying it.

What seems a little less justifiable, however, is the fact that profanity also has a way of creeping its way into their written assignments. For instance, I can recall reading about America "kicking Iraq's ass" in the first Gulf War on several occasions. As I said, I'm willing to give students the benefit of the doubt when they accidentally let a curse word slip in the middle of a heated political debate, but when they're sitting at home in front of their computers and working on a formal essay, I would like to think they could rein in their passions a bit more effectively. Apparently, it's just not that simple.

For now, I think I'll just continue telling myself that my students feel so strongly about the study of political science that they can't keep their overpowering emotions bottled up inside. Yeah, that's the ticket...

October 12, 2003

Tales from the Classroom III: Evaluations

On Friday, I asked for a mid-term evaluation from the students in both of my classes in an attempt to gauge whether or not they're finding our weekly discussion sections helpful. Now, having taught for a few semesters now, I've been conditioned not to expect too much in terms of useful feedback from these evaluations. Students tend to keep their positive comments vague with statements like "Jess is a good teacher" and "I really like this class." On the other hand, when the students actually criticize of the class, their feedback isn't typically all that constructive. For instance, any class that takes place before 10:00AM is guaranteed to have at least three or four students who note on their evaluations that the class "sucks" because it's too early. Still, even if evaluations don't always provide instructors with particularly useful feedback, they're definitely worth conducting for their entertainment value alone. After all, when a student writes in an evaluation that "Jess is really funny in a sarcastic way--like Han Solo in Star Wars," how can you not justify doing them again the following semester?

That being said, I was pleasantly surprised by the amount of useful feedback I received from Friday's evaluations. The comments were positive for the most part, but many of my students offered rather insightful tips on how I might use the chalkboard better, get students who don't like to talk more involved, and bring more current events into our discussions. Plus, several students commented that they liked the new haircut I got the previous day, so that's probably a good thing.

My absolute all-time favorite evaluation, however, came during my first semester as a teaching assistant at Virginia Tech. "Jess is a great first-time teacher," this anonymous student opined, "but I wish that he wouldn't pace back and forth in front of the class like an angry caged bobcat while he teaches." I think I'll have that put on my business cards one of these days: professor of political science/angry caged bobcat. Maybe after I have tenure.

Oh, and for what it's worth, previous tales from the classroom are archived here and here.

August 29, 2003

Tales from the Classroom II

It's the end of another week, and I have a whole new set of great stories from my classes. As I said last time around, however, this is neither the time nor the place to dish on what's going on with the classes I'm currently teaching. Fortunately, there's nothing stopping me from going back a few years and digging up a bit of dirt from my time spent teaching at Virginia Tech. That being said, it's time for another installment of... Tales from the Classroom! (cue theme music)

When I teach, I enforce what some people would call a ridiculously strict attendance policy; that is, I require attendance. The usual counterargument that students are the ones paying the tuition and shouldn't have to attend if they don't feel like it just doesn't hold water with me. After all, my job is to teach them political science, and I simply can't do that if they aren't there. Plus, most of the students aren't paying tuition; their parents are--and I have a feeling that they'd probably prefer to see little Timmy drag himself out of bed for a 2:30PM class if at all possible.

Nevertheless, students find various reasons to miss class on occasion--some of which are slightly more valid than others. I've had students stroll into class for the very first time during the fifth week of the semester and explain that they hadn't made it sooner because they didn't know where the class met. I've had a student miss class because she went with her friends on a snowboarding trip and "didn't think that we'd be covering anything important this week." I've had one student miss class because his brother was busted for dealing pot earlier in the week, and the student was too busy going around to friends and family to collect bail money to make it to our weekly meeting.

I've had a female student go into agonizing detail about very personal medical problems to explain her absence from class. Trust me, a vague note from the university health center would have sufficed. I've also had at least one student try the only excuse under the sun lamer than "I play in a band, and we had a late gig last night," which would be "my roommate plays in a band, he had a late gig last night, and it would have hurt his feelings if I wasn't there." Meanwhile, I once had a student who attended my class on a consistent basis that it turns out wasn't even registered for the course. Apparently, she had heard from a friend that the course was "fun" and decided to attend--just for kicks. But, that's neither here nor there.

Anyway, pouring over the various excuses I've heard from students for their absences through the years, I've arrived at two preliminary conclusions:

1. Alarm clocks malfunction roughly 40 percent of the time--always going off late (if at all) and never early. It's amazing that alarm clock manufacturers can even stay in business given such a poor level of quality assurance.

2. During the course of a semester, the average college student will have at least one grandmother pass away--and quite possibly as many as four. So, if you're an elderly woman with a grandson or granddaughter in college (and you happen to be reading my weblog for some strange reason), I'd strongly recommend that you make sure that your affairs are in order. I'm afraid that you're not long for this world.

August 22, 2003

Tales from the Classroom

I taught my first couple of classes today, and I already have some pretty funny stories to tell about the experience. Unfortunately, I suppose that "professional ethics" bar me from discussing them in this particular venue. So, I'll share a story from my time at Virginia Tech a couple of years back instead. What are they going to do--take away my degree?

Anyway, I had graded my students' first exam and returned them at the beginning of our weekly meeting. Some students didn't perform all that well on the exam, and one student in particular actually began crying when she saw her grade. At first, it didn't bother me too much; I assumed she would stop sooner or later. She didn't. Pretty soon, I was fifteen minutes into the material for the week, and the tears showed no sign of stopping. Every time I would pause to ask the class a question, her audible sobs would make the silence that much more uncomfortable--and it was only getting worse as class progressed. Needless to say, it was enough to leave me a bit flustered and generally out of sorts. Fortunately, things couldn't get much worse, right?

Wrong.

About twenty minutes into the class period, a student arrived late. The kicker? She was already crying when she walked through the door. I would later find out that her boyfriend had broken up with her on the way to class, but I had no idea what was going on at the time. After all, twenty minutes is pretty darn late, but it's not like it's the end of the world. Plus, she actually did well on the exam. Anyway, I tried my best to keep my cool and get back to the material. However, unlike the first crying student who was keeping more or less to herself, this new student actually wanted to participate in the class discussion--despite choking back tears all the while.

"I think that (sniff, sniff) Lenin was trying to say (sob, sob) that capitalism naturally gives rise to (anguished wailing) imperialism."

At this point, I couldn't take it much longer. I had one student who was in tears because she thought she was going to fail the course and another who was obviously upset, but willing to give class the old college try all the same. Meanwhile, my heart was breaking just watching this drama unfold, and I was on the verge of bursting into tears myself. So, I did the only thing that I could think of to do. With about twenty-five minutes left in the period, I told the class that we were going to wrap up early and welcomed anyone who wanted to talk about his or her exam--or anything else that might be bothering them--to join me in my office afterwards.

The moral of the story? If you're ever teaching a class, be sure to return any graded papers or exams at the end of the meeting. Trust me on this one. I still haven't figured out how to stop pre-class break-ups, though. I think the key might be early intervention.

"Each entry more identical

than the last..."

Home

About

Archives

Blogroll me!

Blogroll:

Sponsored by:

Slurm -- it's highly addictive!

Masthead:

Email: jess at wiw dot org

AIM Name: AproposJess

Powered by: Movable Type 2.64

Syndication: RSS / LiveJournal

Content: Copyright 2003-2004